Hope: Living & Loving With HIV In Jamaica

Posted: 07/07/2011 | Author: Cameron | Filed under: Stories | Leave a comment In 2007, poet and writer Kwame Dawes made five trips to Jamacia to learn about the impact of HIV and AIDS there. He talked to both people with HIV and people in the medical community fighting the disease. Based on the stories he collected, Dawes wrote 22 poems, which he calls “anthems of hope and alarms of warning.” Hope: Living & Loving With HIV In Jamaica is a multimedia story that combines those poems with video, audio, images, and music.

In 2007, poet and writer Kwame Dawes made five trips to Jamacia to learn about the impact of HIV and AIDS there. He talked to both people with HIV and people in the medical community fighting the disease. Based on the stories he collected, Dawes wrote 22 poems, which he calls “anthems of hope and alarms of warning.” Hope: Living & Loving With HIV In Jamaica is a multimedia story that combines those poems with video, audio, images, and music.

How It Works

The 22 poems are the focus of Hope: Living & Loving. They are presented both as text and as audio. Dawes himself recites the poems. For nine of the poems, there is also an audio recording of a musical version with the words as lyrics. For four “featured” poems, there is a slideshow version, where each line of poetry is paired with a photo. The slideshow plays in step with Dawes’ recital of the poem and the text appears, line by line, like photo captions. So when the user hears the line “the bodies broken, placid as saints, hobble along the tiled corridors, from room to room,” they see a photo of a man, bent over, walking down the hallway of a hospice.

Most of the poems are linked to profiles of the interview subjects who inspired it. These profiles include one to four short interview clips that deal with particular topics, such as “on accepting those with HIV” and “on sex, sin, and death.”

There are also two longer “infocus” videos that discuss the stigma surrounding HIV in Jamaica and what it is like to live with the disease. These look at the bigger issues involved, providing some context for the poems and the people interviewed

Finally, there is an image gallery of related photos. These photos also appear in the background when other content appears on the screen.

What Works, What Doesn’t

Without judging the quality of the poems themselves, something I am certainly unqualified to do, I can say that the poetry really benefits from the multimedia treatment. It’s an oral form as much as it is a written one. When it is read out loud (by the poet himself no less), the rhythm of the lines come through.

This use of audio doesn’t particularly need a visual accompaniment, but when there is one for the four featured poems, it is generally well done. The images are subtle and don’t compete with the words for the user’s attention. It’s always important for the supporting media form not to compete with the lead form.

The supporting videos that give context to the poetry are all well used. The infocus videos use a variety of footage to talk about two particularly important subjects. The briefer interview clips give the user a personal connection to the various subjects. When someone talks on camera about how the felt when they first found out they were HIV positive, it can’t help but be emotional. And by linking the poems directly to the particular subjects who inspired them, the two forms are connected.

Talking To The Taliban

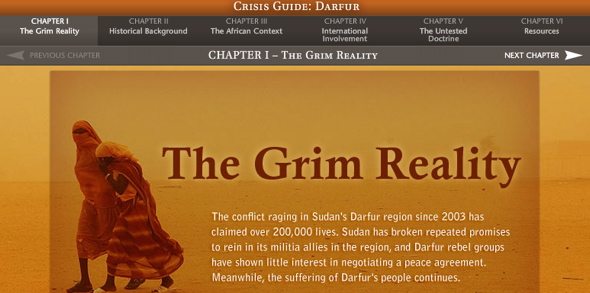

Posted: 06/09/2011 | Author: Cameron | Filed under: Stories | Leave a comment “Understanding the insurgents is a basic part of reporting on the Afghan war, but it’s a remarkably difficult task,” writes Globe and Mail reporter Graeme Smith in the introduction to Talking To The Taliban. Smith’s solution was to send out a researcher, someone with connections to the insurgency, with a camera to interview Taliban members. The footage the researcher brought back – 42 different interviews – is the basis of Talking To The Taliban.

“Understanding the insurgents is a basic part of reporting on the Afghan war, but it’s a remarkably difficult task,” writes Globe and Mail reporter Graeme Smith in the introduction to Talking To The Taliban. Smith’s solution was to send out a researcher, someone with connections to the insurgency, with a camera to interview Taliban members. The footage the researcher brought back – 42 different interviews – is the basis of Talking To The Taliban.

How It Works

The narrative of the project is broken up into six parts: “Negotiations,” “Forced To Fight,” “The Tribal War,” “Pakistan Relations,” “View of the World,” and “Suicide Bombing.” Each part consists of a short video and a text article on the topic. The videos include footage from the interviews with the Taliban as well as shots of Smith himself speaking to the camera in front of ruins or rows of tanks. These interview clips are mixed with other images from Afghanistan as well as graphics and text quotes from a variety of figures. The text offers a sort of deconstruction of the footage for that given topic, with quotes from others referring both to the given topic and the interviews of the Taliban fighters.

In addition to the videos and images, Talking To The Taliban also includes all of the interviews with members of the Taliban, unedited, and an interactive timeline about the Taliban from 1994 to 2008. Five infographics with accompanying text demonstrate the breakdown of tribes in Afghanistan, the number of air strikes in 2007 compared to 2006, the number of suicide attacks in 2007 compared to 2006, the amount of opium poppy cultivation in the country, and the risk to humanitarian operations in the country.

What Works, What Doesn’t

With such rich source material – the interviews with the Taliban themselves – the videos often have a certain raw power. The video quality isn’t great but the men talk directly to the camera, their faces are covered, a machine gun often on their lap. The same can’t be said when Smith is talking. He isn’t the most comfortable figure on camera and he talks in a clipped manner with too many pauses. Sometimes writers are better off writing.

Talking To The Taliban might have been more effective if text had been used to add context with video clips of the Taliban interspersed. The text that accompanies each section covers much of the same ground as what Smith says anyway. Or Smith could have spoken over images and video as the Globe did with Behind the Veil.

And the graphics and other extras, tacked on at the end of the piece, are easily forgotten about. It’s important to integrate extras like these into the main content or at least provide direct links to them.

NYPL Biblion: World’s Fair

Posted: 06/06/2011 | Author: Cameron | Filed under: Stories | Leave a comment Is this how all archives will look in the future? Produced by the New York Public Library, the Biblion: World’s Fair iPad app presents “the World of Tomorrow,” that is, the 1939-40 World’s Fair Collection in the Manuscripts and Archives Division of the library. That collection includes documents, images, films, audio, and essays from and about the famous forward-looking fair, which the app calls a “living, breathing version of today’s unbounded digital landscape, where you could meet foreign people, see exotic locales, experience the world, and find the future.” Forgiving such hyperbole, Biblion: World’s Fair is indeed an impressive experience.

Is this how all archives will look in the future? Produced by the New York Public Library, the Biblion: World’s Fair iPad app presents “the World of Tomorrow,” that is, the 1939-40 World’s Fair Collection in the Manuscripts and Archives Division of the library. That collection includes documents, images, films, audio, and essays from and about the famous forward-looking fair, which the app calls a “living, breathing version of today’s unbounded digital landscape, where you could meet foreign people, see exotic locales, experience the world, and find the future.” Forgiving such hyperbole, Biblion: World’s Fair is indeed an impressive experience.

How It Works

The app begins with a menu of six rather nebulous themes to explore: “A Moment In Time,” “Enter The World Of Tomorrow,” “Beacon of Idealism,” “You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet,” “Fashion, Food and Famous Faces,” and “From The Stacks.” Within each theme are a number of stories, essays, and galleries, each of which pair a certain amount of text, broken into selections, with corresponding photos, documents, images, and the occasional video and audio file interspersed.

The navigation is novel. When the iPad is held on its side, the user can swipe through each page of media, one at a time, from left to right. Turn the iPad for book view, and the same information can be scrolled down through as one large chunk with the option to expand an embedded image or video to full size.

When there is a related story or essay in one of the other themes, the user can follow the “connection” to bring up a blurb about that story and, if they want, read the full story. To browse all the stories, essays, and galleries at once, there is a larger menu with every story listed in which different types of media – audio & video, featured images, document, and connection – are colour coded for easy recognition.

What Works, What Doesn’t

As an historic record, Biblion: World’s Fair is a great resource, touching on a wide variety of topics under the umbrella of the fair and drawing out common historical themes to connect them.

There is a good balance between primary and secondary sources. The essays and stories provide context and understanding while the images and documents help connect the written parts to the time and place. The user doesn’t just read an essay about “Einstein, the Fair, and the Bomb,” they also see photographs of Einstein at the fair and bombshells being moved into the exhibition of the British Pavilion.

The NYPL wisely did not overload the app with either text or archival material. Too much of the first would be far too didactic. Too much of the second would be far too ponderous.

The balance is not as well kept in the mix of media. The vast majority of primary sources are images and documents with only a relative handful of videos and audio clips (although this could be just the source material available). And more often than not, the video and audio content is paired with a short bit of text rather than being integrated into a larger essay.

The navigation works better. When content is organized in a non-linear way as it is done here, the overall experience can easily become fragmented because the user is left to find the common themes on their own. By adding direct connections between essays and stories in different sections that have similar themes, Biblion: Word’s Fair helps the user do this.

This, however, makes much of the content of Biblion: World’s Fair more akin to what you would find in a book than something really innovative.

How Much Is Left?

Posted: 06/02/2011 | Author: Cameron | Filed under: Stories | Leave a comment “If the 20th century was an expansive era seemingly without boundaries – a time of jet plans, space travel and the Internet – the early years of the 21st century have showed us the limits of our small world.” This stark statement begins the introduction of How Much Is Left ?, a Flash-based interactive created for the magazine Scientific American by Zemi, the people behind FLYP. Time, that is, how much time we have before we run out of resources if our consumption levels don’t change, is the focus of How Much Is Left?

“If the 20th century was an expansive era seemingly without boundaries – a time of jet plans, space travel and the Internet – the early years of the 21st century have showed us the limits of our small world.” This stark statement begins the introduction of How Much Is Left ?, a Flash-based interactive created for the magazine Scientific American by Zemi, the people behind FLYP. Time, that is, how much time we have before we run out of resources if our consumption levels don’t change, is the focus of How Much Is Left?

How It Works

Befitting the topic, an interactive timeline is at the centre of How Much Is Left? The estimated lifespans of 16 different resources are tracked from 1976 to 2560. One by one, each resource comes to an end. In 1976 the glaciers start to melt. In 2014, we will hit peak oil. In 2072, we will have used up 90% of the coal available to us. In 2560, we run out of Lithium, a key metal used to make batteries.

At the point on the timeline when each resource runs out, there is an icon to click on that brings up the main content: a pop up with text, a graphic (sometimes static, sometimes interactive), and occasionally a short audio track providing further information about that resource.

The timeline is organized by resource type: 4 minerals, 2 fossil fuels, 2 forms of biodiversity, 2 food sources, and 4 water sources. Each type is colour coded and the user can choose to turn off all but one resource type if they wish.

In addition to the timeline, there are also five documentary-style videos, one for each type of resource, about the depletion of that resource, with related footage and graphics intercut. Finally, there is a poll that asks users whether or not technological innovation will solve the problem of shrinking resources (as of this post, 54% of people said no).

What Works, What Doesn’t

The best thing about How Much Is Left? is that it doesn’t try to do too much. The focus is on the timeline. There aren’t additional sections that might bog down the overall experience. If the user wants further information, the videos corral together different bits of context (expert interviews, related footage and further graphics) in one place for easy watching.

Visually, the timeline works great. Using different colours for different resource types makes it easy to follow the different resources as time goes on. And the dwindling number of lines as time passes certainly makes an impression.

It also works well as a way to navigate through the content. When navigation tools are built into to the content itself instead of being presented in a separate menu, it can add to the overall experience. In How Much Is Left?, the user already knows an important piece of information – the year the resource will run out – before they click on the icon to see the pop up. The only problem is that the user has no idea what that specific resource is until they click on the icon. The only identification given on the timeline itself is the colour indicating what category of resource it is.

However, the pop ups themselves are not so well done. The information varies from overly general, dull text (“Indium is a silvery meal that sits next to platinum on the periodic table and shares many of its properties such as its color and density”) to dense graphs that are not well explained.

It sometimes takes a minute to understand how the information corresponds to the date the resources runs out on. For example, in 2025, some countries will have slightly less water available per capita per year. Why the year 2025 is particularly significant is never explained.

And why audio is used in some pop ups instead of text seems to have been done only to limit the amount of reading the user would have to do. The information presented in each form is pretty much interchangeable in tone and substance.

A Matter Of Life & Death

Posted: 05/31/2011 | Author: Cameron | Filed under: Stories | Leave a comment A Matter of Life & Death is one of 350 stories published by the online multimedia magazine FLYP between 2007 and 2009. At that time, FLYP was an innovative take on the basic magazine idea. Built with Flash, it combined text, video, audio, animation, and interactivity to create “a new kind of storytelling.” FLYP looked like a magazine – the user flipped from one page to the next (hence the name FLYP) and the focus was still on text. But along with the text there was also a variety of different media – animated introductions, embedded video and audio clips, interactive infographics, etc.

A Matter of Life & Death is one of 350 stories published by the online multimedia magazine FLYP between 2007 and 2009. At that time, FLYP was an innovative take on the basic magazine idea. Built with Flash, it combined text, video, audio, animation, and interactivity to create “a new kind of storytelling.” FLYP looked like a magazine – the user flipped from one page to the next (hence the name FLYP) and the focus was still on text. But along with the text there was also a variety of different media – animated introductions, embedded video and audio clips, interactive infographics, etc.

A Matter of Life & Death is a typical example of a FLYP story. It covers a topic that wouldn’t be out of place in any regular magazine: end of life health care. Indeed, the text portion reads like it was published in a magazine. But along with the text there are also video and audio clips, text pop ups with extra information, and links to outside sources.

How It Works

A Matter Of Life & Death begins with a short video intro that sets the tone of the story. “Over a million terminally ill Americans will choose hospice care this year. Insurance companies make billions by denying procedures to patients in need. Still, 54 percent of people believe that reform will lead to rationed care,” read a series of statements between video clips.

On the pages that follow, a complete text story is augmented by multimedia extras. There are “vital statistics” icons that the user has to click on to read. There are video interviews with patients, their loved ones, and doctors. There are roll-over text pop ups that give definitions to key medical terms like “Aggressive Treatment, “Advance Directive,” and “Living will.” There are extra “read more” pages with further information such as the differences between palliative and hospice care. There are links to outside resources for still more reading. There are audio clips of a number of experts speaking about the different dimensions of end of life care.

All of this media is organized like a traditional magazine – one page at a time. On every page there are columns of text surrounded by a mix of different media and hyperlinks elsewhere.

What Works, What Doesn’t

Non-fiction articles in magazines often follow certain style conventions. They begin with a more descriptive scene that illustrates a larger theme and draws the reader in. A mix of descriptive and more informative paragraphs follow to fill out the story and provide greater context. Characters are described and direct quotes given. It’s a flexible style that can be easily adapted for any number of subjects.

A Matter of Life & Death follows this format. The text beings with the case of Maria Cerro, who was admitted to hospital with liver failure. It goes on to describe health care reform proposals under consideration in the U.S. Congress and common misconceptions about “death panels.” There are quotes from a doctor and a Jesuit priest. This is all well and good, as far as it goes. The question is, how do you integrate the media?

The one quibble I have with the overall design of FLYP is in the media integration. Because the text stories are written as complete narratives, the multimedia that surrounds the stories often feels more like extras than integral parts of the story. The reader can happily flip from one page to the next and completely ignore the videos, pop ups, audio, and infographics. You could, of course, consider this to be an advantage rather than a flaw – the multimedia doesn’t get in the way if you’re not interested in it. But it also leaves FLYP with one foot firmly planted in the print tradition.

Ian Fisher: American Soldier

Posted: 05/25/2011 | Author: Cameron | Filed under: Stories | Leave a comment Ian Fisher: American Soldier tracks one soldier in the U.S. Army, from basic training to Iraq and back again. For 27 months, Fisher and those close to him were followed by reporters and a photographer from the Denver Post. They covered his graduation from high school, recruitment, induction, training, deployment, and his return from combat.

Ian Fisher: American Soldier tracks one soldier in the U.S. Army, from basic training to Iraq and back again. For 27 months, Fisher and those close to him were followed by reporters and a photographer from the Denver Post. They covered his graduation from high school, recruitment, induction, training, deployment, and his return from combat.

Ian Fisher: American Solder started as a feature story in the newspaper and was later given the multimedia treatment online.

How It Works

The multimedia shell for the story is divided into four sections according to the type of media: photos, videos, text, and extras.

Within photo and video sections are subsections that follow Fisher’s journey chronologically. There are eight photo slideshow chapters, from “Signing Up” to “Coming Home.” Each photo has a caption that tells the user what they are looking at. The ten videos span the same time frame and feature interviews with Fisher, friends, family, and fellow soldiers.

The story section recreates the original newspaper article, word for word, as a 63-page digital book that users can flip through page by page with a few photographs peppered throughout. The user can also read the story as a scrollable text page on the newspaper’s website.

The extras section includes more video content, lists of Army acronyms and rankings, and an interactive map of U.S. bases in Iraq.

A menu at the bottom of the screen allows the user to navigate between sections.

What Works, What Doesn’t

Ian Fisher: American Soldier isn’t trying to refashion the original newspaper story into a multimedia story. It’s just piling the multimedia content on top. The user has to read the text story first, then look through the photos, then watch the videos, then look at the extras. The different forms of media aren’t integrated together in any impactful way.

That said, much of the multimedia is quite compelling. The photos capture personal moments between different characters while the accompanying captions fill in the context. Browsing from one photo to the next tells Ian Fisher’s story almost as well as the text story does.

The videos are a mix of interview clips and photos. There isn’t any commentary, but they still tell a story. And as I’ve noted elsewhere, commentary from journalists can sometimes hurt the impact of a video. It’s always better to show than tell.

The extras, consigned as they are to their own section, don’t add that much to the overall experience. Should the user want to dig deeper, they’re there, but generally speaking, extras need to be directly linked to from the story itself (as was done in Lifted for example) for them to have any kind of impact or real utility.

Love Letters To The Future

Posted: 05/25/2011 | Author: Cameron | Filed under: Stories | Leave a comment How do you make user-generated content into a compelling overall experience? First, you don’t ask for that much from users. Second, you build a fool-proof template. Love Letters To The Future does both of these things. The site is a collection of letters created by users to the people of 2109 about the threat of climate change.

How do you make user-generated content into a compelling overall experience? First, you don’t ask for that much from users. Second, you build a fool-proof template. Love Letters To The Future does both of these things. The site is a collection of letters created by users to the people of 2109 about the threat of climate change.

How It Works

The letters are either short texts (140 characters or less), YouTube videos, or uploaded images with captions. Users can address one of three topics: “To my Great-grandchildren”, “On Arctic Ice”, or “World Underwater”.

All of the previously submitted letters are available for browsing by date or popularity and users can share or vote for their favourites. The top 100 letters, according to that vote, were sealed in a time capsule, to be opened 100 years from now.

Along with the user-generated letters, Love Letters To The Future also includes a number of featured “first-hand accounts” of climate change from individuals living around the world. Some of these are videos and some are images with captions. There are also videos of celebrities (including, of course, David Suzuki) introducing the topics.

To add a more cinematic element, there are also a number of planted letters ostensibly sent from the future by a women named Maya. Those letters show a planet in decay after nothing was done to stop climate change. Each letter comes with a puzzle for the user to solve in order to find Maya’s next message, giving Love Letters To The Future a game element.

What Works, What Doesn’t

When you rely on users for content, what you get is always going to be a mixed bag. Some of the letters here are truly heartfelt – a message to a still unborn child coupled with an sonogram image for example. Many are dull platitudes – letters that read “Let’s do it!” or “Stop using oil.” Some are just gibberish.

Fortunately, the template does help keep things manageable. Because the amount of content that could be uploaded was limited, the user can easily browse through the letters to find the good ones. And allowing the user to browse by the number of votes a letter has received weeds out most of the less interesting messages.

The advantage of all the user-generated content is the sheer variety of their origin. There are letters here from all around the world, written in different languages (there’s a handy built-in Google translator). There are pictures of people on top of mountains, relaxing on a beach, and tobogganing down a snowy hill. Yes, the sentiment being expressed is pretty much the same in every letter, but the fact that so many people from so many different places all share that same sentiment is at least half the point.

Behind Bars

Posted: 05/24/2011 | Author: Cameron | Filed under: Stories | Leave a comment Behind Bars: The California Convict Cycle, a News 21 project, is a report on incarceration in California. It’s about as sprawling as the prison system it talks about. An introductory video runs through the broader themes addressed: Crime, Race, Control, Change, Life, Death. And while the themes are broad, the individual stories themselves are mostly personal takes on one aspect of an issue, such as one woman’s struggle to make a life for herself after being released, a prisoner serving a life sentence after his third strike, and six different women whose loved ones were murdered. This structure is similar to Soul Of Athens.

Behind Bars: The California Convict Cycle, a News 21 project, is a report on incarceration in California. It’s about as sprawling as the prison system it talks about. An introductory video runs through the broader themes addressed: Crime, Race, Control, Change, Life, Death. And while the themes are broad, the individual stories themselves are mostly personal takes on one aspect of an issue, such as one woman’s struggle to make a life for herself after being released, a prisoner serving a life sentence after his third strike, and six different women whose loved ones were murdered. This structure is similar to Soul Of Athens.

How It Works

Behind Bars is organized into five sections: Beyond the Bars, Dying Behind Bars, Desegregation, Surviving Loss, and History. Each section is made up of one to three individual stories. Each story makes use of different media: A story about a parolee includes a documentary-style video and a text story. A story about sick inmates is a photo essay with captions.

Navigation depends on the section. The desegregation section is an interactive map of the yard at Folsom State Prison. Clicking on a hot spot brings up a new segment about the divisions within the prison population such as being an “other”, prison rumours, and prison politics. Each segment consists of a short audio interview with a convict, a photo gallery, and a text transcript of the audio interview.

The history section follows the Burton Abbott case, a 50-year-old murder conviction that ended in the execution of Abbott. The user is invited to look through newspaper articles and photos from the time before submitting their own verdict on whether or not Abbot was guilty, innocent or it is impossible to say either way.

What Works, What Doesn’t

Because there are so many stories told in different ways using different forms of media, each part needs to be judged separately.

A story about the use of GPS ankle bracelets by law enforcement makes good use of both video and text. The video is more personal – it follows reporter Jude Joffe-Block after she is strapped with an ankle bracelet – while the text is more general – it covers the use of the technology across the state. But the two forms aren’t integrated together beyond the shared topic.

A story about a crack addict named Anthony Woods also uses video and text, but the more personal testimony of Woods on the video is repeated in the text, adding redundancy to the overall story.

More innovative in terms of design is the section on desegregation. The hot spot navigation embedded in the image of Folsom State Prison is an interesting way to access the different sections. The problem is that most of the hot spots seem to be placed in random locations across the yard that have no obvious connection to the topics. Because of this, the navigation doesn’t particularly add to the story in the same way that hot spot navigation does in other stories.

Overall, Behind Bars includes so much content that a larger narrative arc would be impossible to impose. What it loses in cohesiveness, it makes up for in scope.

Soul-Patron

Posted: 05/16/2011 | Author: Cameron | Filed under: Stories | Leave a comment In Soul-Patron, the user follows an animated stuffed animal named Tokotoko around Japan, from a fishing village to a Tokyo supermarket to numerous shrines. Along the way, they learn about Japanese religion, culture, and society. Topics include Mizuko Jizo, the guardian of children, and everyday details about the country such as what to say when exiting a crowded train car, how to use a vending machine, and how to bow properly.

In Soul-Patron, the user follows an animated stuffed animal named Tokotoko around Japan, from a fishing village to a Tokyo supermarket to numerous shrines. Along the way, they learn about Japanese religion, culture, and society. Topics include Mizuko Jizo, the guardian of children, and everyday details about the country such as what to say when exiting a crowded train car, how to use a vending machine, and how to bow properly.

How It Works

Soul-Patron is made up of 34 different locations around Japan. Each location starts with a static video loop. Embedded in the video are multiple hot spots to click on. Doing so leads to a new static video clip with more hot spots to click on. The user goes on clicking until they reach a dead end and have to backtrack or click on the hot spot that leads to the next location (there is usually the choice to skip a couple of scenes along the way if they want to). So at a Kamakura Temple, the user can navigate to video loops of, among other things, an orange tree, hanging lanterns, praying candles, or religious statues. Once they are done with that, they can move along to a video loop of the village of Kamakura where there is plenty of other minutia to explore.

Almost all of these clips include pop-up text boxes that provide more information about what the user is looking at. Occasionally, an animated Tokotoko will enter the scene and tell the user something new (this animation is particularly well done, Tokotoko looks like he’s really in the picture).

There is also background music and related sounds from the scene to bring the videos to life. In this way, the user is supposed to feel like they’re really in Japan, travelling from site to site. An overview menu keeps all of this organized for the traveller, which, frustratingly if you have to start again, doesn’t allow you to click on places you haven’t visited via the hot spots.

What Works, What Doesn’t

Aesthetically, Soul-Patron is beautiful. All of the videos are nicely shot. The very use of looped video adds to the sense of being there. The problem is that nothing really happens in them. It’s just scene after scene of what amounts to still life.

The text that goes with the videos doesn’t help. The information tends to be Wikipediaish in its generality and blandness. For example, the text for Iriya, a neighbourhood in Tokyo, reads in part, “Iriya is an old, peaceful, lowcost area filled with corner shops and mom-and-pop businesses and factories. People live here. They have small plots of land on which they built two- or three-story wooden structures.” And the topics are so diverse that, while the user is taught a little bit about a lot of things, there isn’t anything to draw them into a larger narrative. The only character is Tokotoko, but everything he says is about as bland as the text. When the user finally reaches the last location – the Mizuko Jizo shrine – they might not remember that that was the entire point of the trip.

It’s a shame because the basic idea behind Soul-Patron is novel – a virtual tour. If the creator had narrowed the focus to something smaller than an entire country and had dug up some more interesting facts to tell or included characters the user could have connected with, it could have been an interesting trip. As it is, it’s just a long one.

The Debt Trap

Posted: 05/12/2011 | Author: Cameron | Filed under: Stories | Leave a comment Who’s to blame for the mountains of debt facing so many consumers in America and beyond? The Debt Trap, a Flash-based interactive from the New York Times, attempts to answer this question through a series of videos, articles, slideshows, and interactive graphics.

Who’s to blame for the mountains of debt facing so many consumers in America and beyond? The Debt Trap, a Flash-based interactive from the New York Times, attempts to answer this question through a series of videos, articles, slideshows, and interactive graphics.

How It Works

The Debt Trap is more a way to bring together Times stories and interactives about personal debt than it is an original series. The user navigates between these different pieces through a series of simple, topical sentences in which keywords link to other pages. For example, clicking on the words “drowning in debt” in the sentence “Many Americans, drowning in debt, now face a lifetime of repayment” brings up a text article about Diane McLeod, a women who is indeed drowning in debt. Clicking on “your” in the sentence “How heavy is your debt load?” brings up an interactive graphic that allows you to input your own debt levels and see where you stand compared to the rest of the U.S. according to age and income.

For those who like to see everything at once, there is also an index with every article in the series listed.

What Works, What Doesn’t

A simple method of navigation has both its plusses and minuses. On the one hand, it’s easy to use. The user just reads the sentence and clicks on a link. On the other hand, the whole is pretty much equal to the sum of its parts. Reading the individual stories one after another makes for a rather disjointed overall experience. There isn’t much there to connect the different content together beyond the shared topic. Sentences like “Debt devastates young, middle-aged and older Americans alike” or “Beyond America, credit card use is exploding” don’t add that much context.

Plus, clicking on the text articles sends the user to a separate page on the Times website. Should the user want to return to the series page, they have to start from the beginning.

That said, most of the content is well done. The text articles add context to the reporting. The videos tell the stories of individuals trying to cope with high levels of personal debt. Hearing them tell their own stories gives the issue a personal touch. The interactive graphics such as a timeline that tracks the history of American debt levels communicate further context in a way that isn’t overwhelming or boring. And one graphic allows the user to compare their own debt level to the US as a whole. Only the photo slideshows fail to be compelling (but then, how do you photograph debt?).

Carrie

Posted: 05/12/2011 | Author: Cameron | Filed under: Stories | Leave a comment The opening page of Carrie defines the word, dictionary like, as “1: Derelict blast furnace located along the Monongahela River in Rankin, Pa.” Perhaps the editors at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette were worried that readers wouldn’t recognize the name of one of the last standing but long since abandoned pre-World War II blast furnaces in the U.S.

The opening page of Carrie defines the word, dictionary like, as “1: Derelict blast furnace located along the Monongahela River in Rankin, Pa.” Perhaps the editors at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette were worried that readers wouldn’t recognize the name of one of the last standing but long since abandoned pre-World War II blast furnaces in the U.S.

Carrie the story is about remembering the history of the site. Alongside the definition is an old black-and-white picture of the place with men in fedoras and white shirts standing around. The user can drag a slider across the photo to reveal the same place as it is now, crumbling and covered with graffiti.

How It Works

The story is divided into three parts. The first is an interactive tour of the blast furnace consisting of seven large 360° photos of different rooms. Each one is coupled with an audio interview of someone who used to work at the plant explaining what the user is looking at. The user can control the direction of their gaze within the photo.

The second part consists of four videos that further explain the history of Carrie and the basics of blast furnaces. Topics include “What is a blast furnace?” and “Why are the furnaces important?”

The third part is an interactive timeline that charts the history of Carrie, from its construction in 1884 to its designation as a National Historic Landmark in 2006.

A rudimentary menu connects the parts together.

What Works, What Doesn’t

From the opening definition to the blast furnacing 101 videos, Carrie sure spends a lot of its time trying to convince the user that a blast furnace is worth all this attention. It works better when the content is left to speak for itself.

The 360° panoramas inside the crumbling ruins of America’s rust belt are amazing to look at. The 360° treatment works well with the scale of the spaces and the detail of the machinery. The accompanying audio that explains what each space was when Carrie was still in operation fills in just enough context. It’s about as close as the user can get to actually being there with a tour guide.

The videos aren’t quite as successful. The first, which follows two former Carrie workers as they wander through the site has some emotional punch, but the video that explains what a blast furnace is by interviewing the director of museum collections and archives for Rivers of Steel probably would have been better as a paragraph of text.

And if the Gazette editors were so worried that users wouldn’t even know what a blast furnace was, perhaps the story could have been structured to provide an explanation sooner instead of tucking it away in the video section where it isn’t even the first video listed.

The timeline, meanwhile (like many other timelines), is consigned to its own section, disconnected from the rest of the site.

As it is, the overall narrative is unfortunately quite disjointed. There isn’t enough of a sustained narrative here to draw the reader in. If blast furnaces were so important, Carrie fails to make the case.

Soul Of Athens

Posted: 05/10/2011 | Author: Cameron | Filed under: Stories | 1 Comment Soul of Athens isn’t a single story. It’s not even a single project. Every year, students at the Ohio University School of Visual Communication create a new version of the multimedia project. The topic of each one is a place most people have probably never heard of: Athens, Ohio, population 22,000.

Soul of Athens isn’t a single story. It’s not even a single project. Every year, students at the Ohio University School of Visual Communication create a new version of the multimedia project. The topic of each one is a place most people have probably never heard of: Athens, Ohio, population 22,000.

Five editions have been created so far, each with a different overarching theme. In 2011, it was the changing American dream. In 2010, it was experience. In 2008, it was the pursuit of wellness.

With upwards of 45 different stories in each project, there’s a lot of ground covered in such a small city. Topics in the 2011 version include a taxi driver working the night shift, Chinese students at the university, and young love in a small town. Previous versions included stories about a highway being built, college basketball, bluegrass music, a nursing home, and family farms.

How It Works

Depending on the edition, stories are either organized according to fairly nebulous categories like “Expression,” “Shelter,” “Spirituality,” “Creativity,” and “Youth,” or they are all listed together.

A variety of different media is used, including text, video, photos, illustrations, and audio clips. How that media is used changes with each edition. In the 2010 edition, the stories were usually short videos with only the occasional slideshow, illustration, audio clip, or bit of text. In the 2011 version, each story combined different forms of media together. A story about a man with cerebral palsy starts with a photo slideshow, continues with a text story, and has audio clips of different characters speaking about their lives throughout. A story about our possessions starts with a video, continues with a few paragraphs of text and ends with a photo slideshow.

Different extras have been used in different years. The 2008 version included an interactive map of the area around Athens. The 2010 version included a Twitter feed about Athens (appropriately titled “The Pulse of Athens”) and allowed users to comment via Facebook. A selection of stories from the 2011 version were made into an iPad app.

What Works, What Doesn’t

Soul of Athens isn’t about linear narrative structure. Similar to Behind Bars, it’s a group of individual stories about a particular topic, in this case a place. And even in a city of 22,000 people, there are a lot of stories to be told.

The focus is broad. The rather open-ended guiding themes don’t exclude much – you could probably make the case that just about any story focused on an American living today is about the changing American dream. But generally speaking, these are personal stories centered on characters.

The integration of multiple forms of media in single stories in the 2011 edition is welcome, but there is a certain amount of redundancy. For example, the text and video used for a story about black students at the mostly white Ohio University covers much the same ground. Both talk about culture shock, racism, and Alpha Phi Alpha, the black fraternity. Some of the same quotes are even used in both the text and video. Generally, the stories use traditional approaches to the different forms of media and then stick the pieces together.

The stories that primarily mix text with photos work better, especially on the iPad version where navigating between pages is a breeze and a greater number of photos can be more easily embedded in the story.

So while Soul of Athens lacks some cohesion, both inside the stories and as a package, when all the different parts are taken together, it gives an idea of the diversity even a small city can possess.

Our Choice

Posted: 05/09/2011 | Author: Cameron | Filed under: Stories | Leave a comment Al Gore is pretty media savvy by former elected official standards. He created the sophisticated slideshow that became the subject of the documentary An Inconvenient Truth. He is the co-founder of Current TV. He was given a Webby Lifetime Achievement Award for his role in the creation of the internet. And now he has teamed up with a couple of ex-Apple engineers (the ones behind Push Pop Press) to recreate the book for the iPad age.

Al Gore is pretty media savvy by former elected official standards. He created the sophisticated slideshow that became the subject of the documentary An Inconvenient Truth. He is the co-founder of Current TV. He was given a Webby Lifetime Achievement Award for his role in the creation of the internet. And now he has teamed up with a couple of ex-Apple engineers (the ones behind Push Pop Press) to recreate the book for the iPad age.

Our Choice is a digital recreation of Gore’s book of the same name about, surprise surprise, solutions to the climate crisis. The choice in the title refers to whether or not we choose to take the necessary steps to solve that crisis. The iPad version uses the same text and pictures as the dead-tree one with a number of multimedia additions.

How It Works

Our Choice looks a lot like a traditional text book. There are pages of text that the user flips through, one after another. There are pictures and pull quotes throughout the text. The 18 chapters include “The Nuclear Option,” ” Forests,” and “Political Obstacles” (which pointedly begins with a picture of George W. Bush speaking to Saudi King Abdullah).

What makes Our Choice more than just another ebook are the multimedia extras. Related videos are embedded in the text and expand to full screen when tapped. These are either animations narrated by the wooden sounding Gore, archival news clips, or interviews with experts. Some pictures “fold out” to reveal more of the image while expanding to full screen when tapped. Some pictures include sound clips with the same wooden narration from Gore. All pictures include a link to a Google map that locates both where the picture was taken and where the user currently is. Interactive infographics allow the user to uncover more information by swiping the screen with their finger.

Navigating between these elements from page to page and between chapters involves the tapping, swiping, and scrunching that will be familiar to iPad users.

What Works, What Doesn’t

The backbone of Our Choice is the text with the multimedia playing backup. This isn’t full integration. The users still read it like they would a book. The text, taken from the book version, is complete in itself. The videos, infographics and map are just extras, not integral to the understanding of the whole.

The text is pretty much what you would expect from a text book written by Al Gore. The opening paragraph to the chapter on solar power reads “Electricity can be produced from sunlight in two main ways – by producing heat that powers an electricity generator or by converting sunlight directly to electricity using solar cells.” It just goes on like that for pages – lots of information, not a lot of colour. Text is probably the best form of media for such content.

The videos fare better. Even if the content isn’t that much more lively, at least the user gets to see related b-roll. And in some cases the videos go beyond what text alone could do – a clip of the dense smog in London in the 1950s for example, or a report on the new megacity of Chongqing in China that shows a packed skyline obscured by a haze of pollution.

The interactive graphics standout here as taking particular advantage of the iPad’s touch screen. The user can slide through timelines or adjust variables to see new outputs.

Some of the multimedia extras, however, are less successful. Tagging a picture on a Google map doesn’t really add that much context (as was the case with Lifted) and many of the pictures that Gore adds narration to probably could have been left to stand on their own.

Assignment Afghanistan

Posted: 05/09/2011 | Author: Cameron | Filed under: Stories | Leave a comment “I made my first trip to Afghanistan in October of 2009 when General Stanley McChrystal was just beginning to implement his counter-insurgency strategy, and I wanted to see where the rubber was hitting the road with this very new strategy and at this particularly bleak juncture in America’s involvement with Afghanistan” Elliott Woods tells us in the introduction to Assignment Afghanistan (literally, as the introduction is a video of Woods speaking directly to the camera).

“I made my first trip to Afghanistan in October of 2009 when General Stanley McChrystal was just beginning to implement his counter-insurgency strategy, and I wanted to see where the rubber was hitting the road with this very new strategy and at this particularly bleak juncture in America’s involvement with Afghanistan” Elliott Woods tells us in the introduction to Assignment Afghanistan (literally, as the introduction is a video of Woods speaking directly to the camera).

Assignment Afghanistan, presented by the Virgina Quarterly Review and winner of the 2011 National Magazine Award for Best Multimedia Package, collects the text articles, videos, and photographs created by Woods during his time in Afghanistan (with more articles to come). Topics vary, including foot patrols in the Jalrez Valley, the country’s mining industry, and self-immolation among young women in western Afghanistan.

How It Works

Like other multimedia projects listed on this blog, Assignment Afghanistan is not a single work. It’s a collection of stories connected by a common topic – in this case a rather wide topic, the war in Afghanistan.

These stories are either videos, photo videos with narration by Woods, text articles, or photo slideshows (or a combination of two of these). All stories are self-contained and are not integrated together.

The connections come through the navigation. In addition to a list of stories, Assignment Afghanistan also includes an interactive timeline, starting in 2001, that lists major events in the war in Afghanistan. The stories are also marked on the timeline according to when they were created. A Google map marks the location of the different stories (a smaller map is also included with each story).

The above-mentioned video introduction introduces Woods, the author, and sets the scene in Afghanistan.

Assignment Afghanistan also includes an attempt at public journalism by allowing readers to upload their own writings and photos about the war and life in Afghanistan. These “public stories” have been written by both American soldiers and Afghans.

There is also a page of links to articles by other writers about the conflict that provide further background, analysis, and on-the-ground reporting.

What Works, What Doesn’t

Assignment Afghanistan isn’t trying to be a cohesive narrative. It’s just trying to bring together different content created by Woods and others in a way that is easy to navigate.

In this respect, it works very well. The different stories and photos are easy to navigate between. The interactive timeline and map provide a small amount of context for each one relative to the others and the overall situation in Afghanistan. The video introduction connects the user to Woods, putting a face to the other content.

Although the content is not integrated together, it is all well-done. Woods certainly makes the most of whatever medium he uses. The longer text articles provide a good mix of context and reporting. Larger topics like the Afghan mining industry or the fight over the Arghandab River Valley are covered in this way. Photo videos with narration are used for smaller topics like soldiers out on patrol. When there is more action – soldiers firing on the enemy for example – video is used.

But more could have been done to integrate the different stories together to create a stronger, cohesive overall narrative (Project Jacmal, for example, does a better job of stringing together individual stories by following particular subjects over time). The map and timeline ultimately give only so much context to a user who isn’t already familiar with the war in Afghanistan.

Project Jacmel

Posted: 05/05/2011 | Author: Cameron | Filed under: Stories | Leave a comment While it won a National Newspaper Award in the multimedia feature category, Project Jacmel isn’t a single feature. It’s more a collection of text stories, videos, photo galleries, and blog posts about a single place – Jacmel, a city of 148,000 in southern Haiti that was ravaged by the 2010 earthquake.

While it won a National Newspaper Award in the multimedia feature category, Project Jacmel isn’t a single feature. It’s more a collection of text stories, videos, photo galleries, and blog posts about a single place – Jacmel, a city of 148,000 in southern Haiti that was ravaged by the 2010 earthquake.

Covering an entire city, even a small one, is a tall order (just look at the mileage multiple classes from the University of Ohio have gotten out of the town of Athens). To narrow down the scope, Project Jacmel focuses on seven core subjects: a shopkeeper, a tent city, a hotel, a film student, the politicians and business leaders of the community, a group of artisans, and a church.

For each subject there are different articles documenting the disaster, the rebuild, and the future, which were added over the course of the year following the earthquake, allowing the reader to follow the slow rebuilding of Haiti through different characters.

How It Works

The user can browse through lists of text articles, videos, and photo galleries sorted by subject matter (the aforementioned seven, plus another section of articles about the city one year after the earthquake, and stories that didn’t fit elsewhere under the heading “more stories”).

A sidebar provides information about the project, a selection of important numbers (the number of dead, the number of houses destroyed, etc.), and a link to the Project Jacmel blog, which includes shorter, more informal posts about the city’s recovery as well as extra photos and videos.

The Globe opted to present the content of Project Jacmal like any other content on its website instead of building a separate Flash space for it as they had done with Behind The Veil and Talking To The Taliban.

There is also a menu that allows the user to browse content by media type.

A Google map shows where all of the subjects are located in the city, and also links to that content.

What Works, What Doesn’t

There is a ton of content here. So much so that it can be difficult for the user to find their way around.

The problem is the navigation. Trying to tie together so many stories without building a separate site to house them can make a jumble of things. The pages for the seven subjects list all of associated content in parts, but it isn’t always clear which parts are about the disaster, which are about the rebuild, and which are about the future. And there are often more than one piece of content listed as “Part 1” or “Part 2”. It’s all a bit confusing.

This problem doesn’t help the overall narrative. Following a single subject is easy enough. But where do the extra articles fit in? And what about the blog posts? Finding the larger narrative of Jacmel beyond individual shopkeepers, politicians, or artisans is left to the reader.

The stories themselves are well-done. Different types of media are well-used. The text articles add wider context while the videos tend to be more personal. When a shopkeeper says on camera that she doesn’t know what she’s going to do because her husband is sick and can’t help her, the user can see the uncertain look on her face. But because each part was created to stand on its own there is a fair amount of overlap in the type of information covered by the videos and text articles.

But what Project Jacmel lacks in cohesiveness and ease of navigation, it makes up for in scale. With so many pieces published over such a long period, readers can put the pieces together to get a very vivid picture of place and time.

Anticipation On A City Block

Posted: 05/05/2011 | Author: Cameron | Filed under: Stories | Leave a comment Anticipation On A City Block goes all the way back to Obama’s inauguration in 2009 (it seems so long ago now). The New York Times interviewed the residents of a single Washington city block “where two churches for decades symbolized the nation’s racial divide.” The story is a snapshot of that divide today after the election of the first black president.

Anticipation On A City Block goes all the way back to Obama’s inauguration in 2009 (it seems so long ago now). The New York Times interviewed the residents of a single Washington city block “where two churches for decades symbolized the nation’s racial divide.” The story is a snapshot of that divide today after the election of the first black president.

How It Works

The Times interviewed 14 people, both black and white, from the block. For every subject there is an audio clip, a series images, a brief text description of who the person is and where they came from, a text quote, and a headshot of the person.

In the audio clips, the subjects talk about the inauguration, Obama, the history of the neighbourhood, and/or race relations in America. While the user is listening, images of the subjects at home or at their church flip by on auto advance.

On the navigation page a 2D image of every building on the street pops up with the pictures of the subjects underneath. When the user moves their cursor over a subject’s picture, the building they live/work in is highlighted. Move to another street and the buildings pop down one at a time with new ones popping up to replace them. A small 3D model of the entire block at the top of the page allows to user to keep track of where they are spatially.

A short video introduces the story.

What Works, What Doesn’t

The design of Anticipation On A City Block is quite similar to Beyond The Stoop, another Times interactive feature. Like that story, the information presented here isn’t deep. Rather, it’s a quick look at how a group of regular people feel about an historical occasion. Whether or not they have something profound to say isn’t really the point.

To this end, the audio clips are short and personal. They don’t go far beyond a minute in length. Subjects talk about wanting to hug people, how super excited they are about going to the inauguration, how difficult it is to find a parking spot. These kinds of comments sound better when the actual people say them. In print, they would be dull. And combined with photos of the people inside their own houses, the audio makes the story more personal.

The navigation is probably the most innovative element. The way buildings pop up and down and become highlighted when the user moves the cursor over a picture gives the entire design a dynamic feeling. There’s always a place for dynamic design.

Waterlife

Posted: 05/02/2011 | Author: Cameron | Filed under: Stories | Leave a comment There is no doubt that the Great Lakes are important. We drink the water in them. We ship goods via them. We sail on them. But are the Great Lakes interesting? That’s harder to say. And yet, Waterlife, a Flash-based multimedia interactive about the Great Lakes created by the NFB to complement the documentary of the same name, is interesting. It’s amazing what a slick navigation system and the right mix of media can do for a topic.

There is no doubt that the Great Lakes are important. We drink the water in them. We ship goods via them. We sail on them. But are the Great Lakes interesting? That’s harder to say. And yet, Waterlife, a Flash-based multimedia interactive about the Great Lakes created by the NFB to complement the documentary of the same name, is interesting. It’s amazing what a slick navigation system and the right mix of media can do for a topic.

How It Works

Waterlife begins with 23 different definitions for “water.” Water is history. It’s neglect. It’s power. It’s healing. It’s in you and me.

Clicking on a definition brings up a text quote which gives way to a series of short bits of text on the topic. Depending on the section, either a looped video plays in the background behind the text (the text can be hidden to get a better look at the video) or the user can interact with a virtual desktop (complete with movable paper clips, sticky notes, and photos). There is the occasional interactive graphic, pop up with more information, or link to an outside website for further information.

While the user is reading, one or more anonymous audio sound bites (which one assumes are from the documentary) play in the background along with soothing music (Sigur Ros and Philip Glass are included on the soundtrack).

There are different ways to navigate through Waterlife. Along with the list of “What Is…” definitions, there is also a navigation bar at the bottom of the screen made up of a series of blue vertical lines that rise and fall like a wave as the user passes their cursor over them. There is also a map of the Great Lakes made up of small photos that acts as a sort of contents page. Click on one of the pictures and the map breaks apart like a school of fish swimming together and reforms into shapes that relate the topic chosen.

What Works, What Doesn’t

While the combination of text, video, interactive elements, and sound bites may sound like a lot of information to take in at once, every element is kept short enough that the user can shift their focus from one thing to the next without much difficulty. Single pages of text aren’t usually more than a few paragraphs and the sound bites are only a few seconds long.

The downside of this is that only so much information is presented in any given section. And with 23 different topics that cover everything from fishing to pollution to dredging, the user never gets more than a cursory look at the various issues affecting the Great Lakes. Should they want to know more, they have to follow the links and leave Waterlife.

Furthermore, the information that is presented can be rather technical. Paragraphs begin with “Many experts believe that…” or “There are approximately…” The sound bites are left anonymous so the user doesn’t know who is speaking. There are no characters to connect to. This makes Waterlife a rather impersonal experience, a problem when the subject matter is already so technical.

The overall narrative thrust is not strong. While every section is about the Great Lakes, they don’t connect to each other beyond the common topic. The sections come in an order, but there’s no real reason to follow it. Indeed, the user doesn’t have to. They can just click on one of the pictures that makes up the map of the Great Lakes to randomly access one of the topics.

Where Waterlife does better is with overall tone. Much care was taken with the design and navigation of Waterlife to give it a suitably fluid, tranquil feel. The way images come together like fish. The soothing music. The cool colour pallet used. It all evokes the feeling of actually being in the water.

The Big Issue

Posted: 04/07/2011 | Author: Cameron | Filed under: Stories | Leave a comment The Big Issue opens with a statement and a question: “Human kind is getting fatter. Why?” This French Flash-based multimedia documentary travels two continents to investigate the global obesity epidemic. There are stops in France, California, Quebec, and Belgium. The user learns about bariatric surgery, the glut of fast-food restaurants in underprivileged neighbourhoods, and the difficulties in imposing top-down government solutions to the problem of obesity. In this way, they can investigate the global obesity epidemic from the comfort of their own couch.

The Big Issue opens with a statement and a question: “Human kind is getting fatter. Why?” This French Flash-based multimedia documentary travels two continents to investigate the global obesity epidemic. There are stops in France, California, Quebec, and Belgium. The user learns about bariatric surgery, the glut of fast-food restaurants in underprivileged neighbourhoods, and the difficulties in imposing top-down government solutions to the problem of obesity. In this way, they can investigate the global obesity epidemic from the comfort of their own couch.

How It Works

The Big Issue is designed to be an immersive experience. The user doesn’t just watch the documentary – it is as if they are right there, asking the questions and deciding where to go next. This is done with a sort of “choose-your-own-adventure” style of navigation. At different points during an interview, a choice of questions will appear at the bottom of the screen. For example, during an interview with an obese Frenchman, the user has the choice of asking “Do you think you’re responsible for your weight problem?” “Do you watch a lot of television?” or “Are many of your family members obese?” When the user clicks on one, the interviewee’s response to that question plays. When the user grows tired of asking questions, they are given a choice of where to go next.

Visually, The Big Issue is mostly a series of photographs of the different places the user goes to and the people they meet. There is also the occasional video. The responses of interviewees are usually audio only. Music or ambient noise plays in the background. All other information, such as where the user is, who exactly they are talking to, and statistics about obesity, appears as text.

From time to time, the user can click on a pop up for extra information related to their current location. There is also an obesity map that tells you what percentage of a given country is obese, highlighting the global scale of the problem.

A complete menu allows quick navigation between locations, handy if the user wants to backtrack if they miss something.

What Works, What Doesn’t

The novel “choose-your-own-adventure” style of navigation is suppose the make the user feel like they are in control of the narrative, but it can also be rather frustrating. The number of questions the user can choose between is limited enough that the user still often feels like they’re being led through the documentary, but plentiful enough that they can often miss something and have to backtrack to get the full story. Ultimately, the conceit that it is the user visiting these places and talking to these people is a weak one. It is one thing to include interactivity in a web documentary but it is quite another to create a completely immersive experience.

More successful is the mix of media used. Using audio for interviewee responses and text for contextual information nicely separates the personal and the impersonal. The combination of audio responses, ambient sounds, and photographs creates a strong sense of place. And when videos are used, they are often used very effectively. For example, a video taken in Los Angeles from a moving car passing one fast-food restaurant after another emphasizes the fact that healthier options are often hard to come by.

For Want Of Water

Posted: 04/06/2011 | Author: Cameron | Filed under: Stories | Leave a comment The Las Vegas Sun multimedia interactive For Want Of Water begins with a depressing thought for the people of that city: “With expected changes in climate and no change in future water usage, Lake Mead could run dry by 2021.” And if that statement wasn’t enough to get the user’s attention, there’s a counter next to it, counting down exactly how much time Lake Mead has left to the millisecond (3589 days, 2 hours, 45 minutes, 51 seconds at the time of writing). How did Las Vegas get in such a jam and what can the city do about it? Those are the questions For Want Of Water looks into.

The Las Vegas Sun multimedia interactive For Want Of Water begins with a depressing thought for the people of that city: “With expected changes in climate and no change in future water usage, Lake Mead could run dry by 2021.” And if that statement wasn’t enough to get the user’s attention, there’s a counter next to it, counting down exactly how much time Lake Mead has left to the millisecond (3589 days, 2 hours, 45 minutes, 51 seconds at the time of writing). How did Las Vegas get in such a jam and what can the city do about it? Those are the questions For Want Of Water looks into.

How It Works

For Want Of Water is essentially a video series plus. The story is primarily told by five short videos a few minutes in length each. There is a shorter introductory video, one about the over-watering of lawns, one about a proposed pipeline to feed the growth of the city, one about pumping water out of the desert, and one about balancing growth and sustainability. The content of each video is pretty much what you would expect from a current events doc – a mix of talking heads, footage from water treatment plants, dessert pipelines, and other important locations, b-roll, and narration.

Accompanying the videos is a Bing map that marks the exact location of whatever place the video is talking about. There is also an info box that gives extra information such as what exactly the Colorado River Compact is and how fast Clark County’s population is growing. Occasionally there is an extra video to watch in the info box that will pause the main video when played, or link to another website. The user can also read pop-up text bios of onscreen interviewees as they talk (but only when they’re talking). These three extras are triggered as the main video’s timeline progresses.

The user can navigate between videos using a menu on the right side of the screen.

There are also links to related articles from the newspaper.

What Works, What Doesn’t

With so much going on at once, it can be difficult to take in everything. While the main video is playing, all of the extra information can easily go unnoticed. The user can manually control the info box if they missed something, but the embedded links to outside pages and the extra videos disrupt the flow of the main narrative. The problem is the choice of media. Video demands the user’s full attention. Looking away to read a related info box can break that focus.

That being said, the video content is interesting. Interviews with experts are broken up with suitable b-roll. When the video discusses the over-watering, the camera follows a Las Vegas Water Authority investigator as he patrols the city looking for water waste. There are nice closeups of the water flowing off a lawn down the street.

The Bing map, however, only adds useful information when larger geography is mentioned.

Perhaps For Want Of Water would work better as a television news piece. But then, it was produced by a newspaper.

A Year At War

Posted: 04/01/2011 | Author: Cameron | Filed under: Stories | Leave a comment A Year At War is a massive undertaking with the kind of scope only a major publication like the New York Times could manage. It follows the men and women of the First Battalion, 87th Infantry of the 10th Mountain Division over an entire year of deployment in Afghanistan, from March 2010 until March 2011. Quite a few topics are covered, both big and small. Soldiers pray, receive mail from home, go out on patrol, train Afghan police, play the guitar, exercise, and trade fire with insurgents. They talk about what they miss from home, what they fear, and why the joined the army.

A Year At War is a massive undertaking with the kind of scope only a major publication like the New York Times could manage. It follows the men and women of the First Battalion, 87th Infantry of the 10th Mountain Division over an entire year of deployment in Afghanistan, from March 2010 until March 2011. Quite a few topics are covered, both big and small. Soldiers pray, receive mail from home, go out on patrol, train Afghan police, play the guitar, exercise, and trade fire with insurgents. They talk about what they miss from home, what they fear, and why the joined the army.

How It Works

New content was constantly being added . Because of this, there isn’t one single narrative. Rather, A Year At War is a collection of shorter elements, mostly videos, about Afghanistan and what it’s like to be a soldier there.

The content is divided into three parts. The first, “Going To War,” covers life in Afghanistan. There are seven “features” about important aspects of the mission such as building trust with locals and the trails of leadership. Seven “shorts” consider smaller topics like the death of a soldier and the war dogs the battalion adopted. Nineteen “moments” offer brief glimpses into life in Afghanistan, presented without commentary or cuts. Users are free to browse through these videos according to type, or to watch a curated playlist in chronological order.

The second part, “The Battalion,” is a series of video interviews with both U.S. soldiers and Afghan National Police. They talk about the mission, things that have happened to them in Afghanistan, and issues from home. The user can browse either by individual soldier or by topic.

The third part, “Dispatches,” includes pictures, emails, and messages submitted by the soldiers themselves.

There is also a map of northern Afghanistan for geographical context and a list of links to related articles and multimedia on the New York Times website.

What Works, What Doesn’t

A lot can happen over an entire year. The amount of content here makes other non-linear narratives like Out My Window feel relatively concise. A good editor could probably make a feature-length documentary out of A Year At War. As it is, it’s up to the user to sift through the various bits and pieces and find the story.

For this reason, good navigation is vital. And while it’s not difficult to get around A Year At War, it’s also not always clear what to click on next. The first section has a curated playlist of clips ordered chronologically, which helps. But the second section gives users a list of 34 different soldiers who each talk about a variety of different things, everything from being promoted to the loss of a fellow soldier. Fortunately for the user, for each solder there are links to related content from the first and third sections to fill in a little more context.

But by using individual small clips, A Year At War is able to highlight not just major events but also the little moments that give a fuller sense of place. The 19 “moments” might have been lost in a larger narrative. Presented as individual videos, they demand attention from the user.

A Year At War is first and foremost a visual story, mostly made up of videos and images. Aside from the user-submitted writing and related Times articles, text only appears in captions. This approach fits the subject matter. A Year At War isn’t trying to explain the war in Afghanistan to users. It’s trying to give a sense of what it’s like to be a solider in that war.

To this end, the video content is very well done. Not only does it look great (something newspapers don’t always manage when they try to use a new type of media), it also has impact. The user can watch soldiers talking about their experiences. They can watch intense moments, such as a Taliban ambush recorded by a helmet-mounted camera. They can watch moments of life in the base.

The content submitted by the soldiers themselves adds to the personal connection. A Year At War really does connect the user to the soldiers of the First Battalion, 87th Infantry of the 10th Mountain Division.

Welcome To Pine Point

Posted: 03/21/2011 | Author: Cameron | Filed under: Stories | Leave a comment Part personal memoir, part cultural study, part profile, Welcome To Pine Point tells the story of a northern Canadian mining town that doesn’t exist anymore. When the mine closed down, the town did too. What happened to its people? What is a community? What are memories? These are some of the questions the story asks.

Part personal memoir, part cultural study, part profile, Welcome To Pine Point tells the story of a northern Canadian mining town that doesn’t exist anymore. When the mine closed down, the town did too. What happened to its people? What is a community? What are memories? These are some of the questions the story asks.

This multiple Webby-award winner has gotten a fair amount of well-deserved attention (see here, here and here).

How It Works

“This was supposed to be a book” the authors explain on the “about” page. They were developing a concept for a book about the death of the photo album but they ended up making Welcome to Pine Point instead.

The basics of the book are here. The story is divided into chapters. The user flips from page to page as they would in a book. There’s a linear narrative. But Welcome To Pine Point goes far beyond the traditional book form. While text drives the story, there is also every other type of media you can think of: photos, videos, audio clips, graphics, cartoons (both still and animated), and music. On almost every page, there is something to watch or listen to.

Welcome To Pine Point is designed to look like a scrapbook with text made to look like it was cut out from a different page and glued on top of the videos, animations, or photos. In one chapter, a series of photo collages are a mix of actual photos and looped videos.

There is basic interactivity throughout: text can be pushed aside to give the user a better look at the picture underneath, badges can be moved around the screen, cards can be turned over to reveal more information, and photo slideshows can be clicked through.

Much of the media starts automatically when the user flips the page. Video loops and short audio clips of subjects talking play without any play button being clicked.

Instrumental music by the Besnard Lakes continuously plays in the background, setting a contemplative if slightly sombre mood.

What Works, What Doesn’t

Welcome To Pine Point does a better job of integrating different forms of media together than any other project on this blog. Three things help with this. First, there is never too much media on any given page. At most, there’s a little bit of text (which appears line by line) combined with a short audio clip or two and a short video loop in the background in which nothing much happens. It doesn’t overwhelm the user.